Nils Bergman travels the world advocating for mothers and newborns and warning about the long-term effects of birth practices, as well as their influence on physical and mental health for the rest of their lives.

After birth, under ideal circumstances, sophisticated processes occur at the physical, emotional and neuronal levels, producing bonding and synchronization between mother and baby, which are fundamental for an optimal development of the baby, for the link between both, for the development of the brain social and for long-term health. For these processes to occur some basic conditions are required that nature provides if the situation allowes it: a delivery process as little interfered as possible, preserving the maximum natural hormonal status of birth and allowing the mother and baby to be together skin to skin after birth without interruptions.

However, a great majority of babies are born and are received in very different conditions, either because they are born in environments of unnecessary medicalization of childbirth, or because they are separated at birth. What happens with these babies? What opportunities do mothers have to “repair” what did not happen during and after birth?

In many hospitals in the world this important moment is not being respected, many mothers and babies are separated, or have medicalized births or problems that alter this delicate moment after birth. What are the consequences on a large scale of hindering birth and contact between mother and baby?

We are experiencing huge increases of learning disorders when infants come to school, and a wide range of emotional and behavioural disorders, not least autism. We are seeing poor health in toddlers and adolescents. We are observing an epidemic of Syndrome X: obesity, hypotension and diabetes. In fact, there is a whole new science called DOHaD: Developmental Origins of Health and (Adult) Disease. That birth impacts on this is incontrovertible, but it also comes with bad practices in pregnancy and in the whole neonatal period (first month).

How does a “bad birth” affect adaptive behaviors?

But it may also impact adaptive processes. Adaptation to a benign and good world is called a ‘slow life history strategy’. When resources are poor and things are tough we need a ‘fast life history strategy’. With bad birth practices, the earliest signals the brain gets about the world into which it is born is that this is bad and difficult and tough world. This leads to preparatory brain changes for such a harsh world. It can make the individual as an adult behave adapted to a bad world, even when the world is good. Or, that behaviour might even make the good world become bad, if most people develop into that adaptive behavior.

Imagine a mother who had a difficult delivery, or a cesarean, or has given birth in a hospital with obsolete protocols, and was separated from your baby for several hours. What would you say to this mother? Is it possible to “repair” a bad birth?

Can a ‘bad birth be repaired’? Yes and no. What I have described as the ideal matters because we must provide services that are in harmony with ‘Mother Nature’. But Mother Nature knows that the real world is never ‘ideal’. And so we have something called ‘redundancy’ … anything really important has back up plans. If plan A doesn’t work, plan B or plan C is in place. So it helps to know these. Having an elective Caesarean means you do not get the oxytocin surge necessary for activating the right start to the brain. But immediate skin-to-skin contact can provide oxytocin (plan B), and also suckling at the breast (plan C), helped by Zero Separation after that (Plan D). The result can be quite perfect. A Caesarean as such does not have to be a bad thing at all, unless it is done too early or too late. There is research evidence that it does harm mothering behaviour, but I strongly believe it is the after-Caesarean separation that does harm, not the Caesarean itself.

One or even two bad things does not necessarily lead to harm. It is the accumulation of several bad things (this is called allostatic load). A word of caution: some babies have ‘high sensitivity’ and can suffer harm sooner. And some comfort at the same time, other babies seem to be highly resilient and do not suffer any adverse effects. And there is a spectrum between these groups.

And mothers are different when they come to give birth: some have resilience and good experiences that compensate for inadequate systems. But other mothers may come to birth with past hurts, or never have been mothered themselves, and they need systems that support them.

There is also the timing: several hours will not be as bad as several days, and several weeks is much worse.

Back to our mother in the question above: If we do the right things at the right time, we quickly get a good result. When there has been a delay, we first need to make that delay as short as possible. Then we need to spend much longer and be more careful in providing the support to achieve the good outcome.

Can harm be “repaired”? Yes, always! However, the repair may be costly and time consuming. The repair might be fully functional, but it might leave scars and even suboptimal functioning. “Perfection can be the enemy of the good” … there is no need to aim for perfection. This is however no reason to provide health services that actively prevent perfection, that we know will cause harm. The less our professionals and our care systems provide support, the more likely it is that adaptations and vulnerabilities will be expressed.

The role of breastfeeding

We know the thousand benefits of breastfeeding on the physical health of the baby and his mother. Can you explain how it influences brain, psychic and social development?

Breastfeeding contains nutrients that meet the needs of the body and the brain. But the brain is a “social organ”, and so breastfeeding feeds the sociality of the brain. It does so at many levels, starting with pure one way sensory inputs that make the circuits in the brain form and work. In the process it defines a platform of trust, based on mother always meeting all baby’s needs. Then comes two way sensory interaction which is the fabric of sociality. Emotional connection is the essential ingredient. This engenders “knowing the mind of another”, a definition of empathy and the source of morality. Certainly, empathy and morality can come to some who never breastfed, but it comes much easier and more naturally to many more with breastfeeding.

Now imagine a mother who wished to breastfeed but found many problems, didn’t receive adequate help and finally could’nt breastfeed. What would you say to that mother? Is there a way to compensate for a short or non-existent breastfeeding?

There is a loss from not breastfeeding. This mother did wish to breastfeed, and she deserves sympathy and understanding for her own feelings about this loss. But for her baby, the loss is far from total, and compensation mechanisms are available – as I explained above about redundancy, plan B and plan C are needed. But careful thought is required to ensure the prolonged contact that comes with feeding, and making sure it is pleasurable and fun for the baby and the mother, not just a chore or a task. And the sensory environment of breastfeeding can very well be provided by Zero Separation … prolonged skin-to-skin contact for some weeks until the baby does not like it, and after that prolonged carrying in a sling for many months. And with this lots of singing and reading stories. Einstein apparently said: “If you want an intelligent child read stories. If you want a very intelligent child, read many stories.”

Nils Bergman was interviewed by Isabel Fernández del Castillo

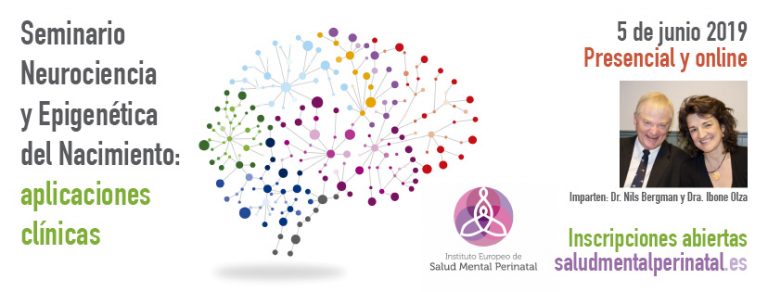

On June 5, 2019 Nils Bergman will be in Madrid to give his course:

Neurosience and Epigenetics of Childbirth: clinical apllications (in english, with consecutive translation)